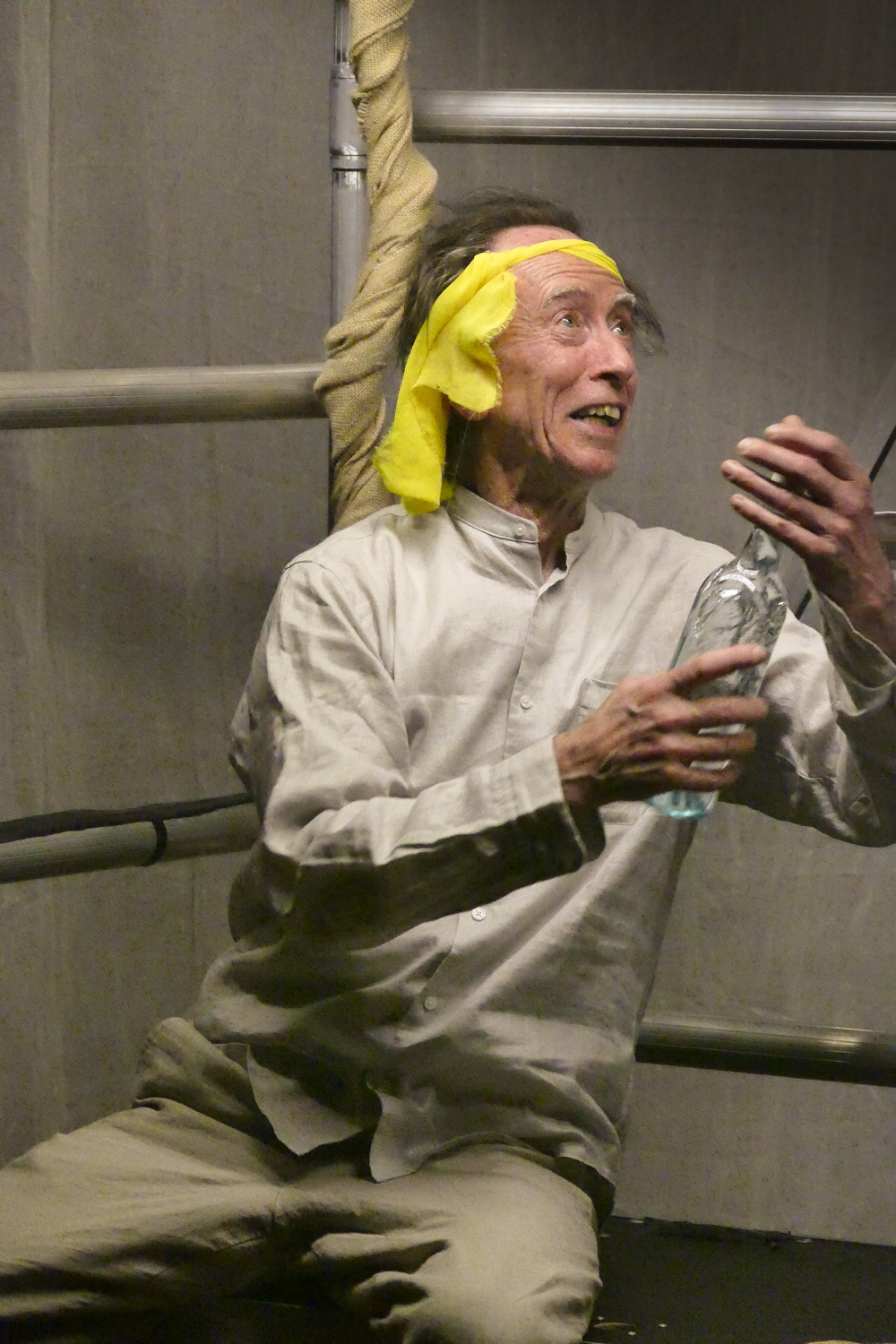

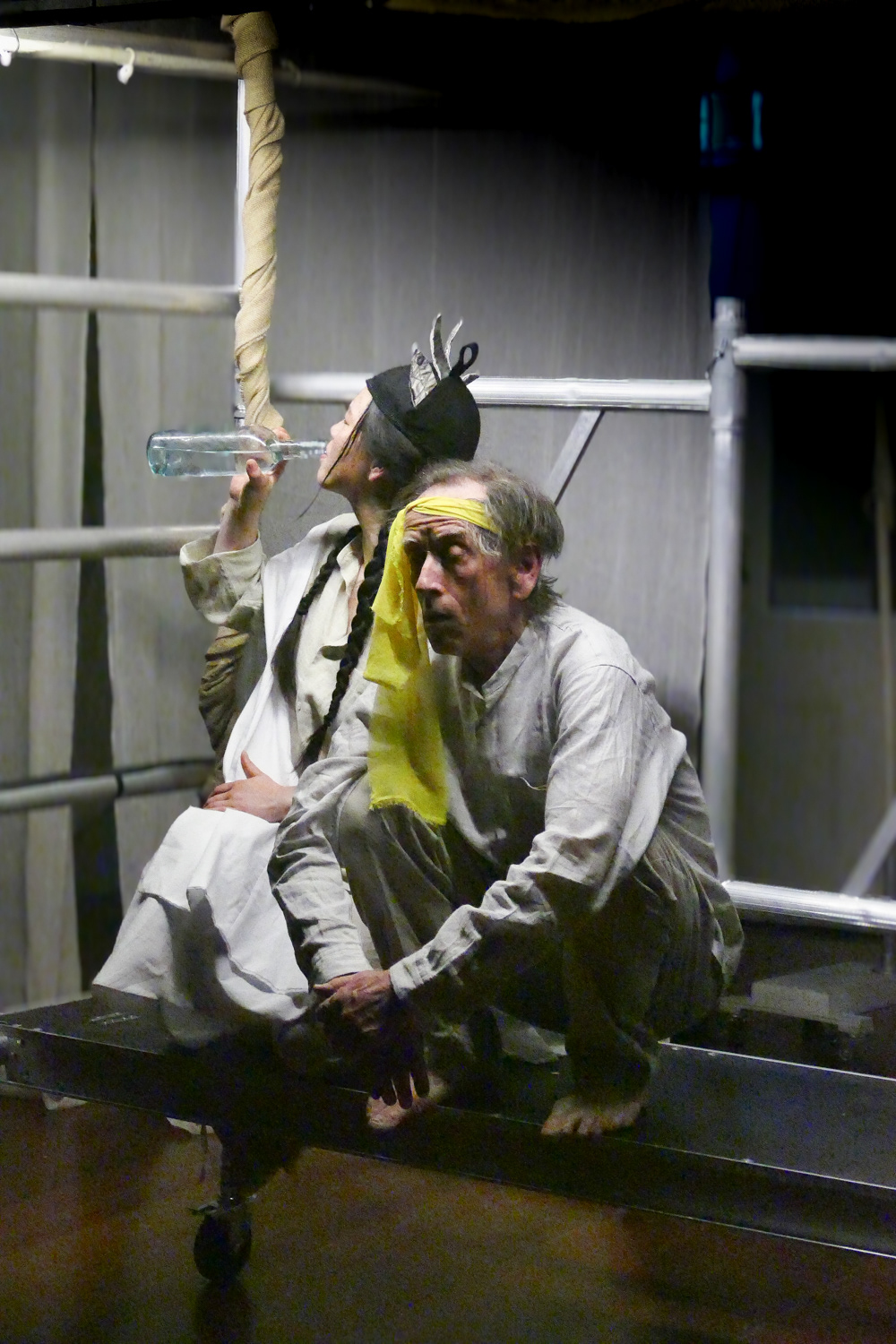

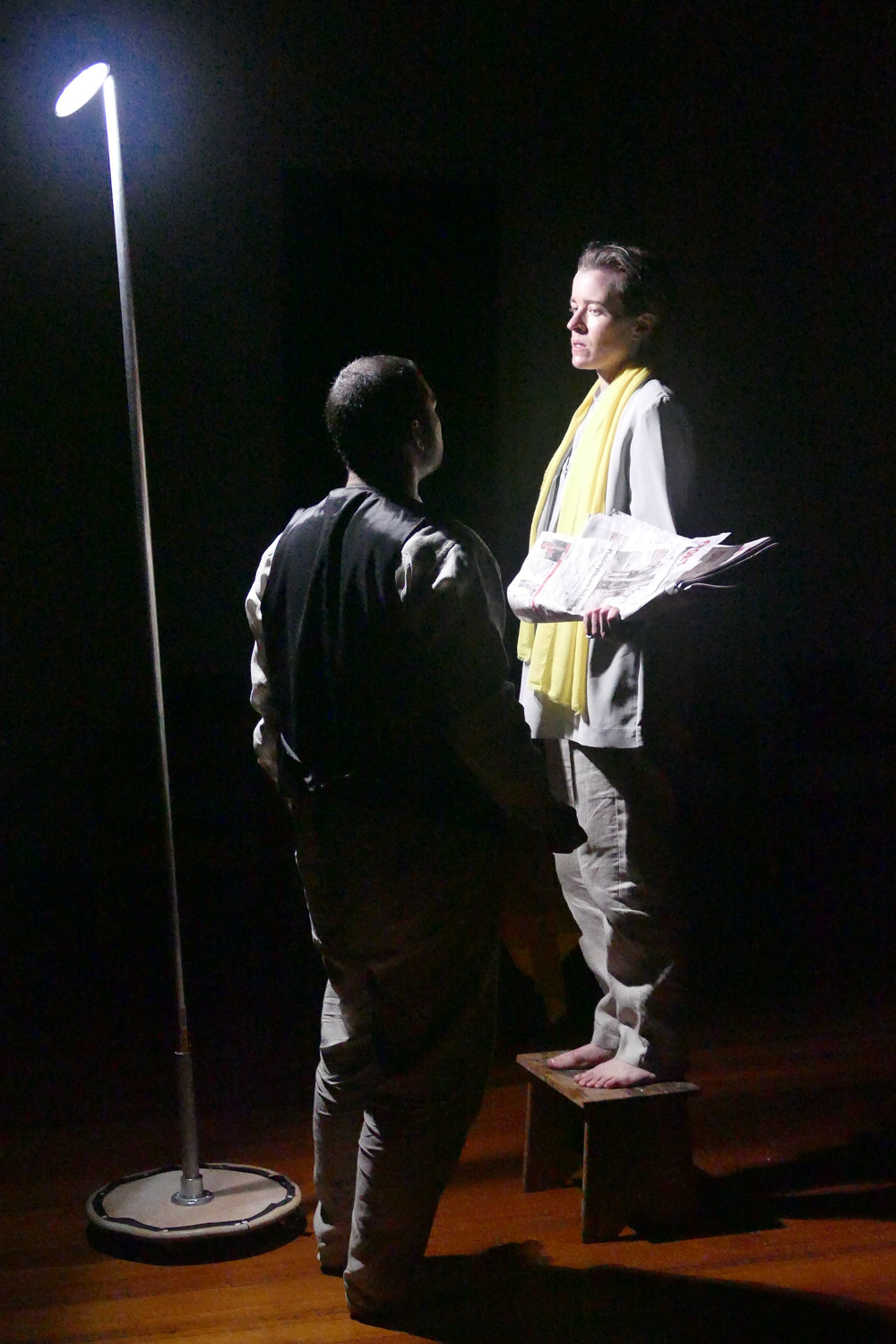

Matthew Crosby 20251005

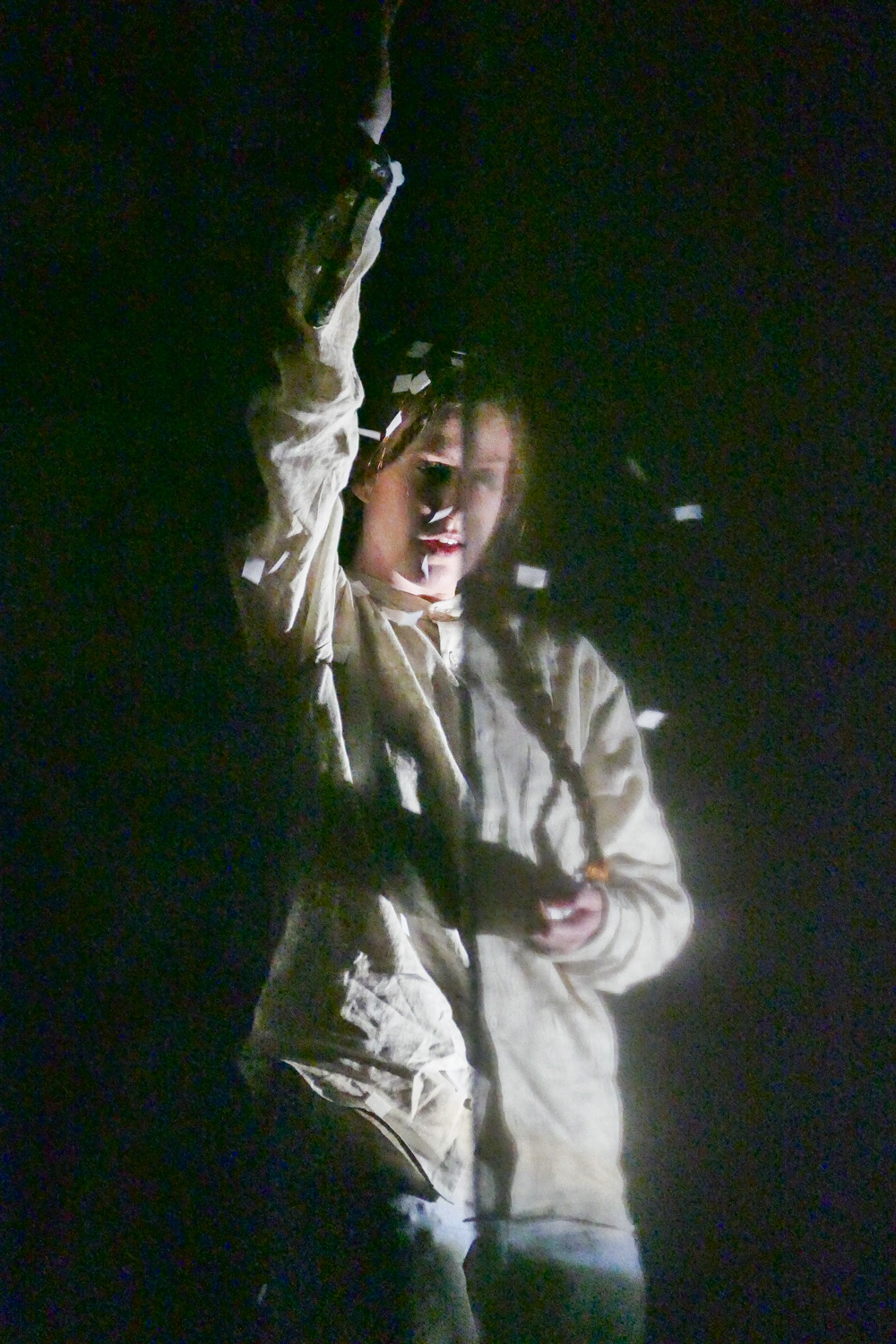

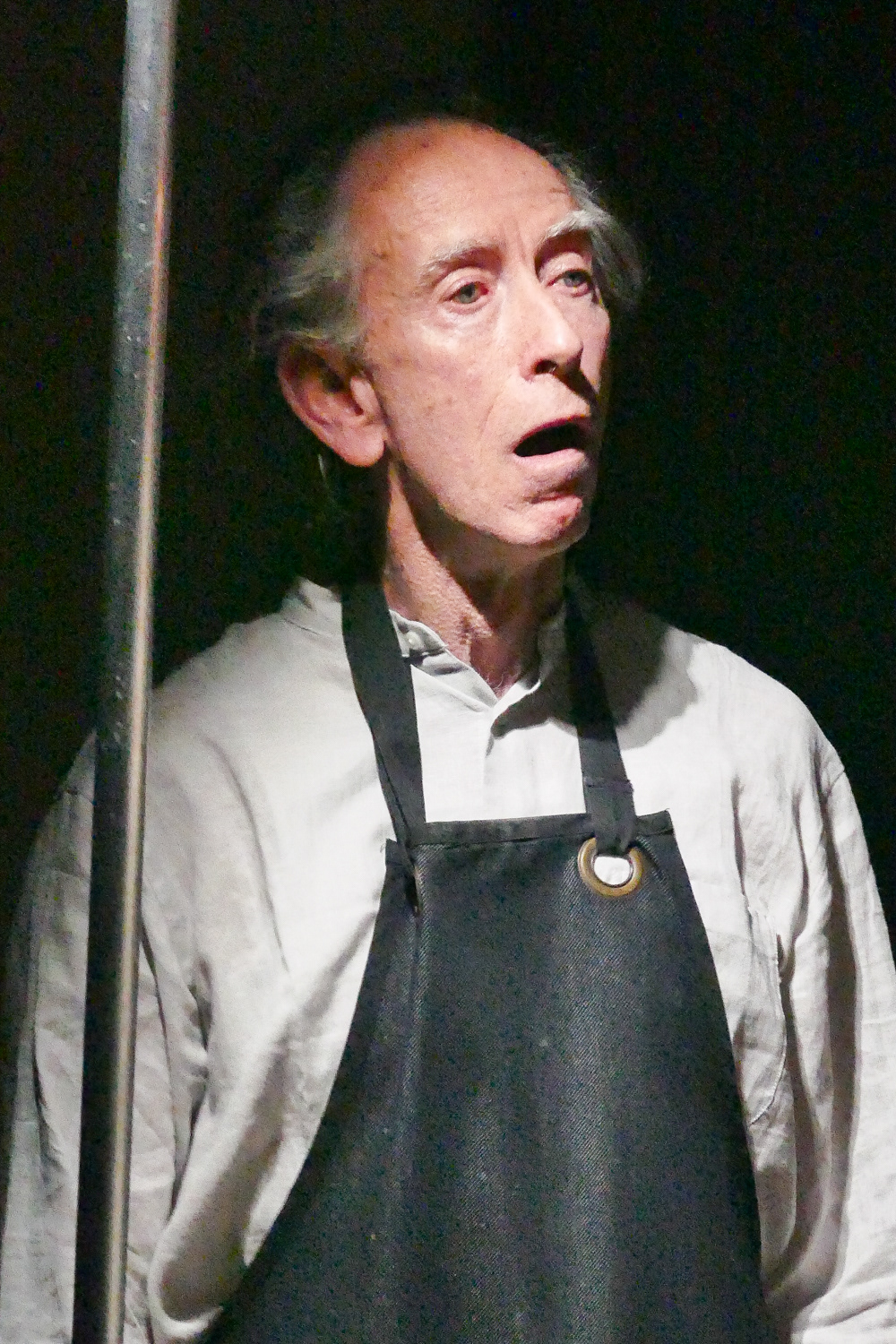

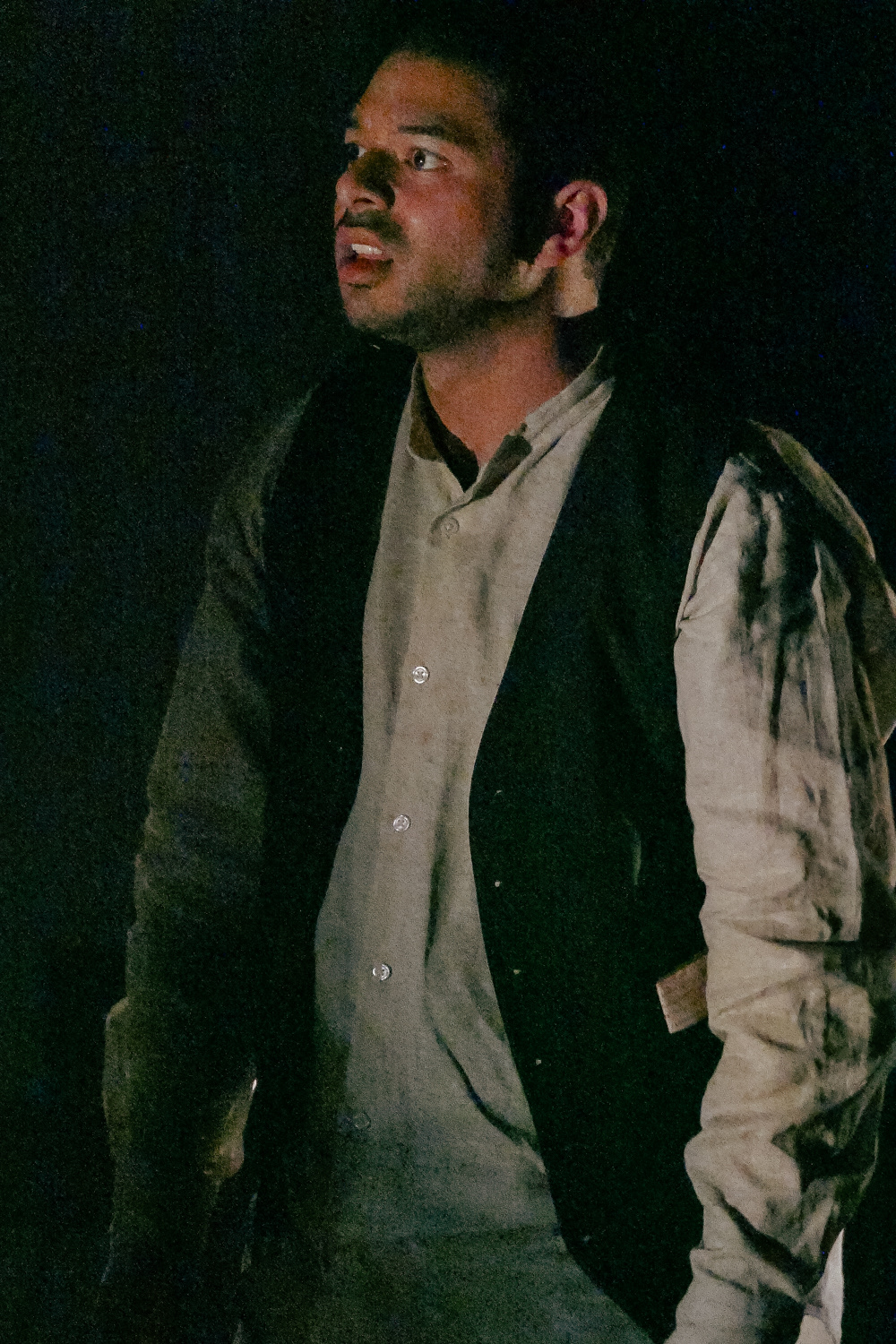

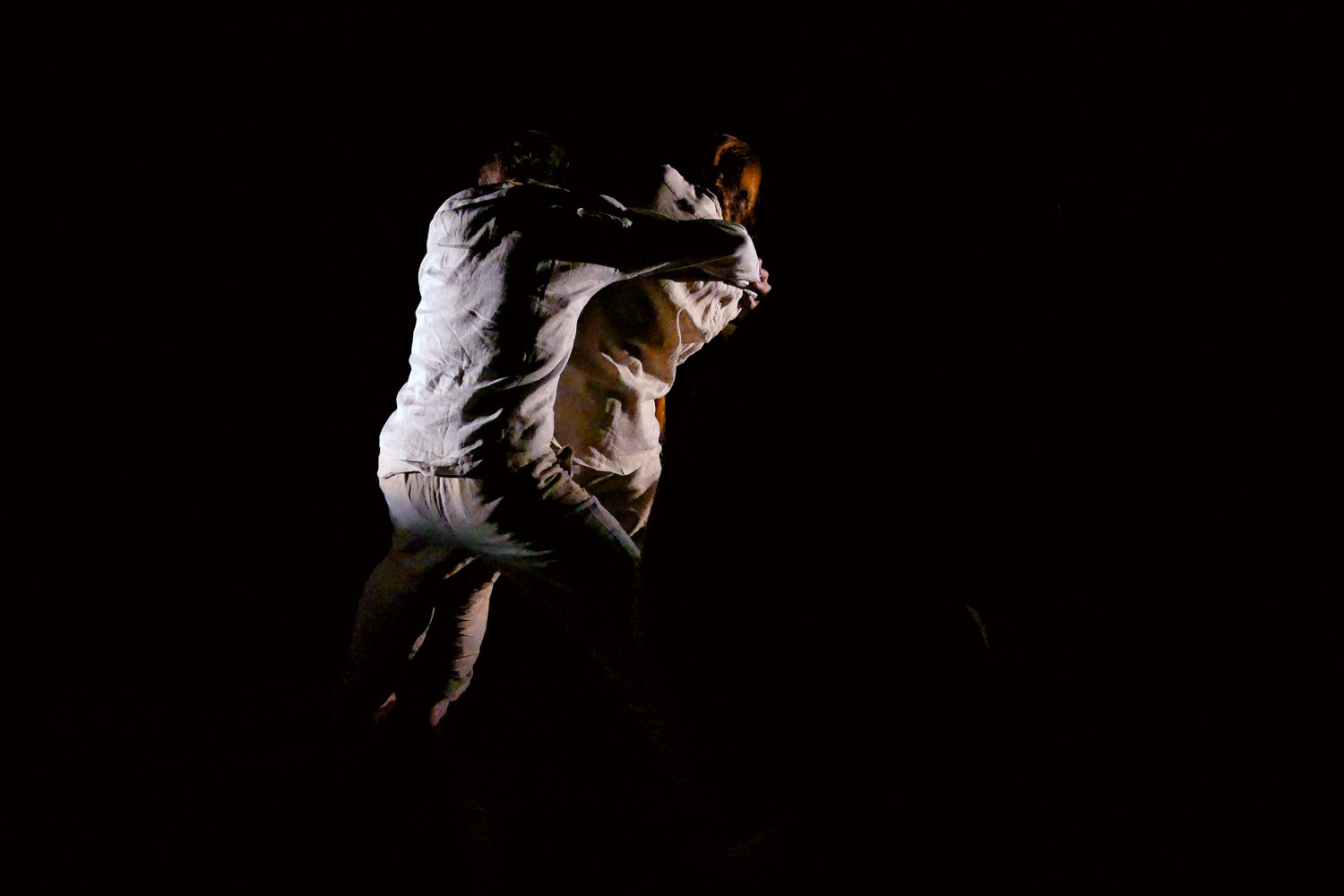

Photos: Joe Calleri

Falling Heads arises from Akutagawa Ryunosuke’s war story written in 1917, The Story of a Head that Fell Off. It’s set during the first Sino-Japanese war of 1895 in which Japanese forces occupied the Chinese Liaodong Peninsula. At the end of the story, the Japanese military officer says to the Japanese Legate,

“It is important–even necessary–for us to become acutely aware of the fact that we can’t trust ourselves. The only ones you can trust to some extent are people who really know that. We had better get this straight. Otherwise, our own characters’ heads could fall off like Xiao-er’s at any time. This is the way you have to read all Chinese newspapers.[1]”

Akutagawa’s self-reflective bias that portrays a Japanese occupying soldier mistrusting the account of an occupied Chinese county newspaper is intentional. So, although Falling Heads follows the circumstance of war and occupation, its main concern asks the question ‘who wins when the story is lost?’. David Rutledge introduces Mariana Imaz-Sheinbaum’s notion of historical multiplicity as a ‘species of narrative’ in which the historian doesn’t ‘discover the meaning of the past but constructs it[2]. In the interview, Imaz-Sheinbaum considers any event as able to be interpretable by any of the people who experience the event. By extension, the story of that event that is passed down can never be seen as a ‘true’ account. Falling Heads, then, is a meditation on the ways that foundational stories of culture can become propaganda.

In this way, our play is a metaphor of past attempts at colonisation, or in the current examples of Gaza and Ukraine or indeed the current (connected) saga unfolding in the United States. Considering the narratives that are told through the problematic tools of social media, what were once wild fringe ideas have become the orthodoxies of malicious sociopaths instated as authoritarian leaders.

Falling Heads is a co-devised performance. In September 2023, I brought Akutagawa’s story into our beautiful North Melbourne studio, and we shared a reading of it. In line with my attempts at uncovering the equality that Jacques Ranciére tells us we should suppose exists between collaborators, I asked our team to state images from the story that resonated with them and to suggest ways we might work with them[3]. So, although I have ‘collated’ this play, which includes rewriting transcripts of improvisation, sequencing scenes and writing a good deal of text from scratch, the play and its themes were derived from a collective voice.

Over the next twelve months, we conducted a series of exercises that developed our dramaturgy arising from Akutagawa’s story.

One memorable evening I made the ground rules (enabling constraints) for an improvisation.

Each player enters and must speak without pause. If they stop or hesitate, the audience of other collaborators applaud loudly, and the player makes an exit. The words from Akutagawa’s story ‘I am cut’ and ‘head’ and ‘off’ must be spoken.

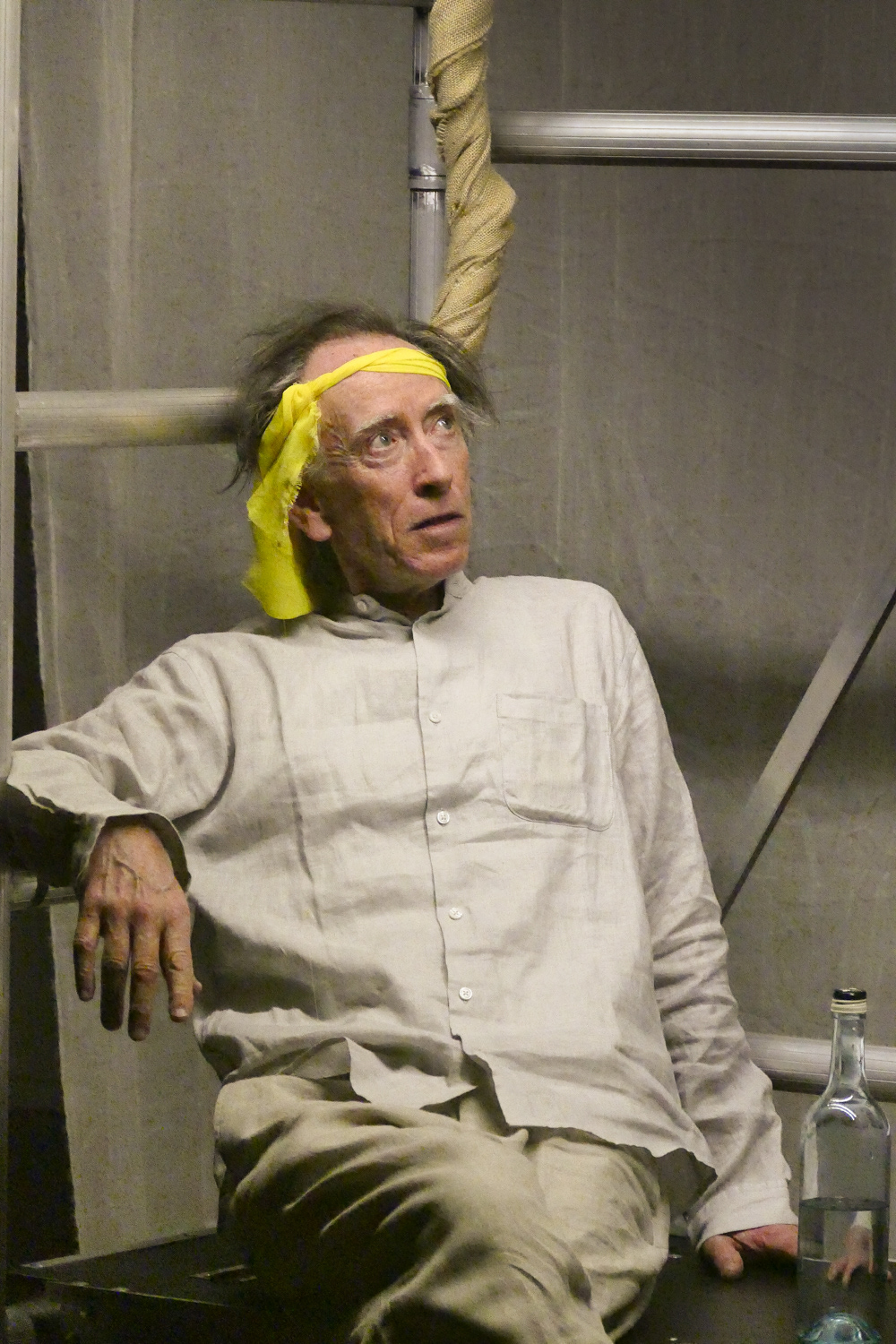

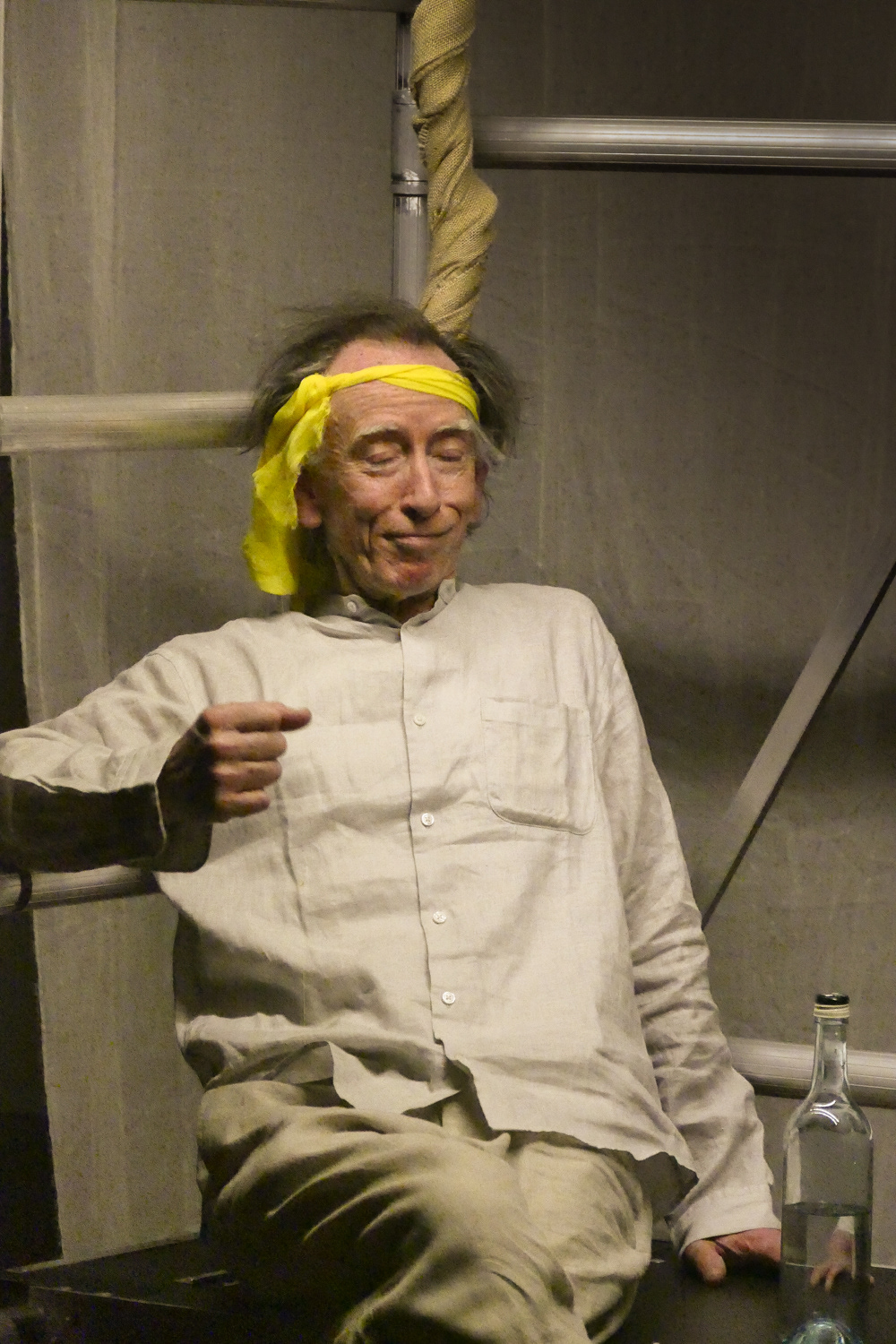

From that one improvisation, two central planks of the story were born. Damon Branecki conceived what would become his character Tomasz’s phenomenologically drenched story in which he wonders, ‘How am I having the thought that my mind is over there’; secondly, Taka Takiguchi told a story in which the account of heads being cut off was questioned… he said something like, ‘There was blood on the ground but whose heads were cut? I can’t remember if my grandmother said it was the boars’ heads or the heads of sunflowers’. Combining these offers, our story became a split between two tribes come of one body and our dramaturgy, a philosophical split between phenomenological (Boar) and Cartesian (Sunflower).

But why these images? How did they relate to the impasse between mind-jockeying-body and the inseparable soul-body? I wanted to honour the improvisation from whence the images originated but found it difficult to marry to our wartime story. In research, I came across Sara Heinemäa’s chapter examining the well documented disagreement between Cartesian mind-body duality and Maurice Merleau Ponty’s lived body perception known as phenomenology[4]. These are foundational philosophical concepts concerning the position of humans—do we understand our existence by the computations of the intellect, or, as is my view, by the ever-growing experiences of embodied perception of the world. The image of the sunflower, so tall and slender, as if it were reaching for some higher order and the earthiness of boars so connected to the wholeness of themselves in nature seemed to be appropriate. It was just one step further to look at the dominance of the idea of the mind as a computer that deals with the world as finite bits to consider that the sunflowers might use their mathematical pure thought paradigm as a tool of oppression. Paolo Freire sees both oppressor and the oppressed as dehumanised by oppression[5]. In the same way, Falling Heads is an allegory for the self-defeating programmes of colonisation where the sensorially oriented Boars are inculcated with the Sunflower orthodoxy of pure thought—both lose their humanity.

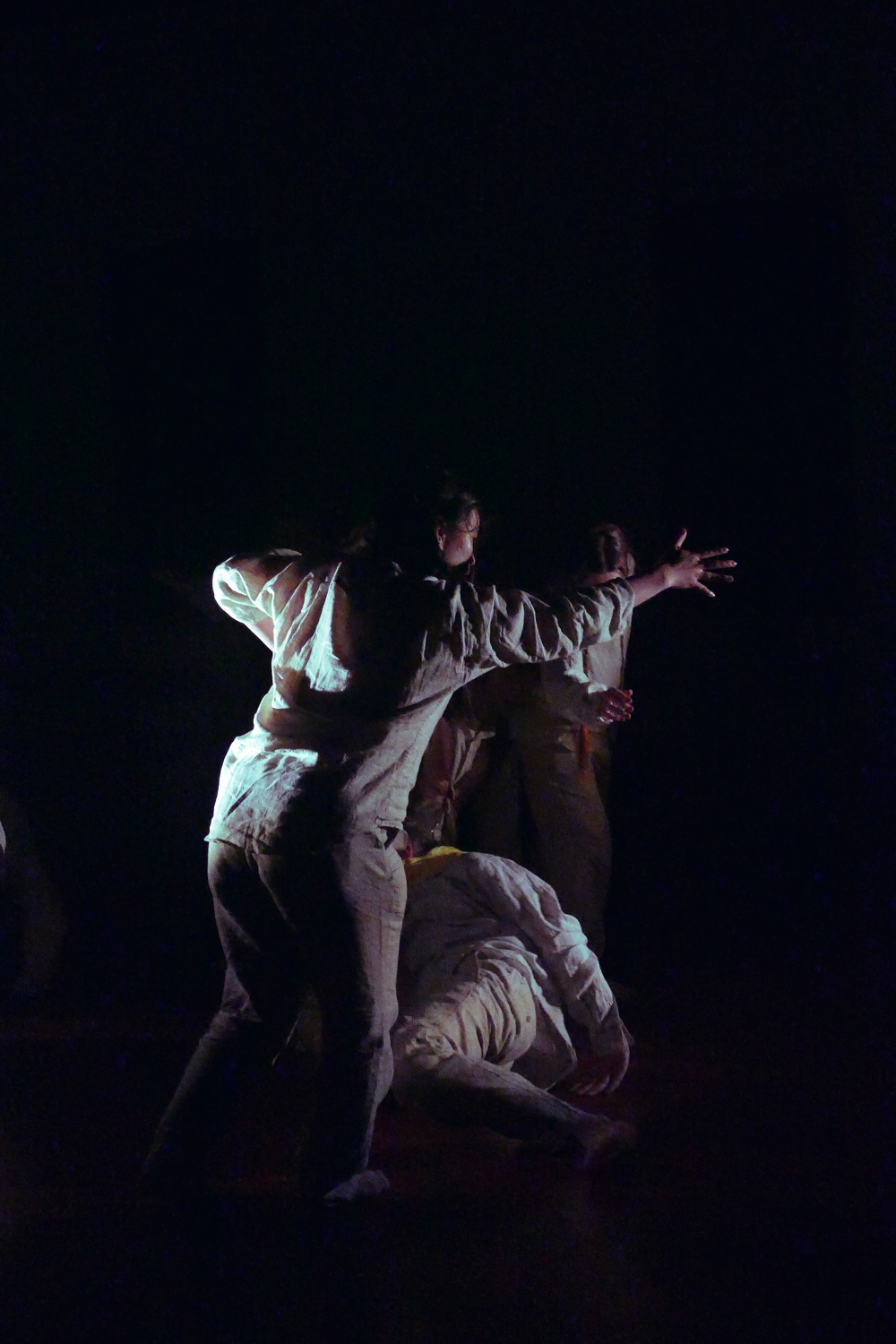

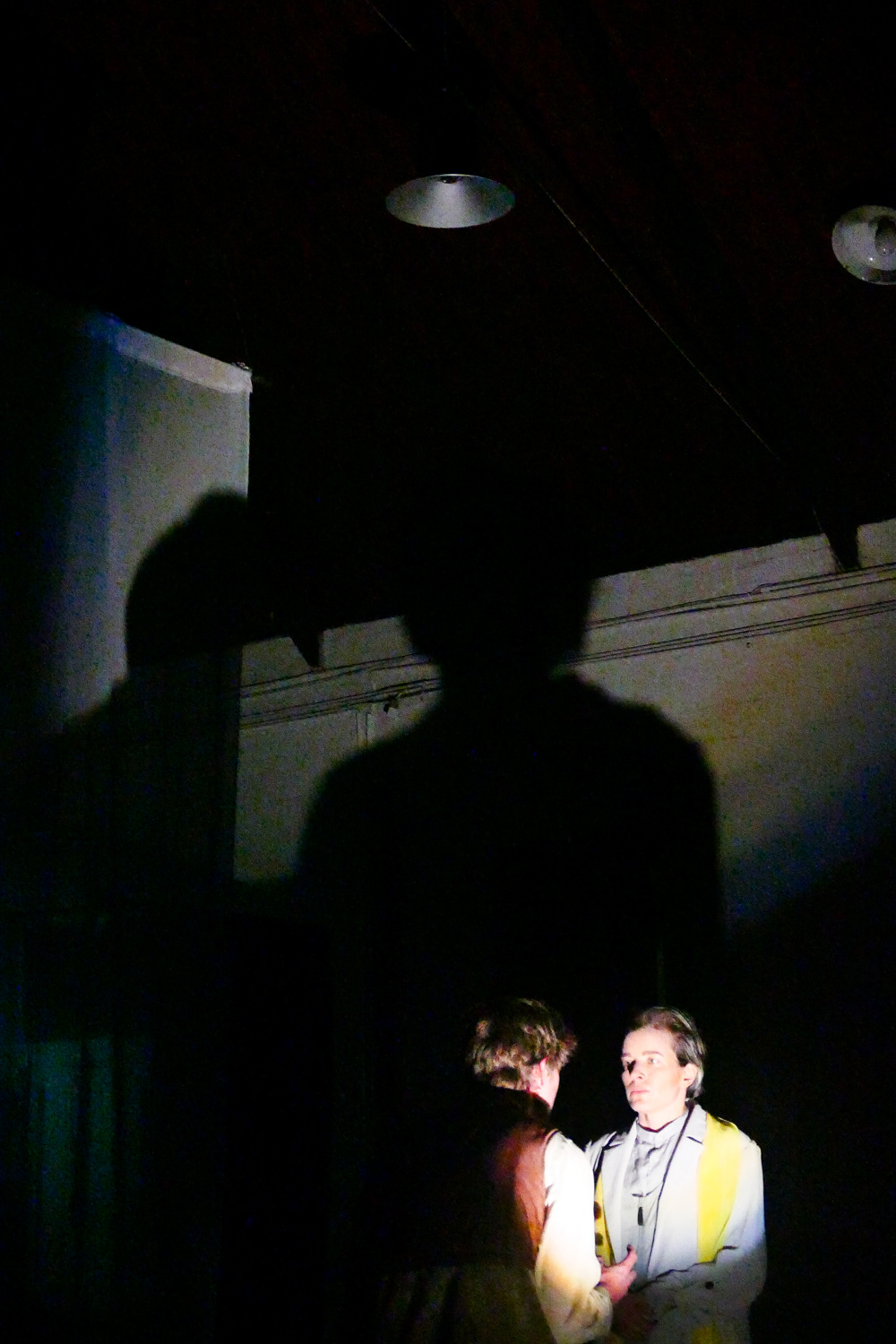

In Falling Heads, you might find various influences. There is no question that the group’s foundational Suzuki Method of Actor Training informs our performance-making in various ways. It is seen in presentational modes used, but also in moments of energetic stillness, or in the sculptural body forms employed. We have also done a lot of work with Grotowski, especially in considering the notion of impulse. Polish theatre group Pieśń Kozla forms part of our practice of embodied intonation. There are two scores used in developing the choreographic foundations, what I have called Touch/Press and Gravity. Touch invites actors to offer | recognise | experience | separate. It is an attempt to articulate the mechanics of actors’ relationality. This was extended to consider battle sequences in Press by increasing the pressure of Touch. Gravity came from my attempt to form actor movement as inter-relational. By which I mean that one actor will in some way orbit another based on physical or psychological attraction and repulsion. These two forces are affected by the energy, mass, momentum and inertia of the bodies. Given the point of our story concerns the notion that it is the victor that writes the history, the political influence of Brecht is inescapable.

Fables are interpreted according to the experience of the audience. Falling Heads might be interpreted as speaking to Gaza, Ukraine or the bellicosity of the U.S., or it might refer to the related culture wars with such signifiers as the ‘technomony’ of Musk, Bezos, Zuckerberg, Theil and the rest, the closure or ‘debiasing’ of humanities faculties or even Trump’s self-appointment as Director of the Lincoln Centre. Whether geo-political or cultural, I think Falling Heads is a cry to reclaim our voice from those few who control the formation and distribution of fascistic narratives.

Akutagawa, Ryunosuke. ‘The Story of a Head That Fell Off’. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Japan Focus, vol. 5, no. 8 (2007). https://apjjf.org/-Akutagawa-Ryunosuke/2489/article.html.

Biesta, Gert. ‘Don’t Be Fooled by Ignorant Schoolmasters: On the Role of the Teacher in Emancipatory Education1:’ Policy Futures in Education, ahead of print, SAGE PublicationsSage UK: London, England, 10 January 2017. Sage UK: London, England. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210316681202.

Heinämaa, Sara. Merleau-Ponty’s Dialogue with Descartes: The Living Body and Its Position in Metaphysics. 2003.

Rancière, Jacques. The Ignorant Schoolmaster : Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation. Stanford University Press, 1991. UniM Giblin Eunson 370.1 RANC. https://www.sup.org/books/cite/?id=3009.

Rutledge, David. ‘History and Narrative’. Philosopher’s Zone, 2 July 2024. https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/philosopherszone/history-and-narrative/103956074.

[1] Ryunosuke Akutagawa, ‘The Story of a Head That Fell Off’, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Japan Focus, vol. 5, no. 8 (2007), https://apjjf.org/-Akutagawa-Ryunosuke/2489/article.html.

[2] David Rutledge, ‘History and Narrative’, Philosopher’s Zone, 2 July 2024, https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/philosopherszone/history-and-narrative/103956074.

[3] Jacques Rancière, The Ignorant Schoolmaster : Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation (Stanford University Press, 1991), 138, UniM Giblin Eunson 370.1 RANC, https://www.sup.org/books/cite/?id=3009.

[4] Sara Heinämaa, Merleau-Ponty’s Dialogue with Descartes: The Living Body and Its Position in Metaphysics (2003).

[5] Gert Biesta, ‘Don’t Be Fooled by Ignorant Schoolmasters: On the Role of the Teacher in Emancipatory Education1:’, Policy Futures in Education, ahead of print, SAGE PublicationsSage UK: London, England, 10 January 2017, Sage UK: London, England, https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210316681202.